Until recently, we expected the 10-year Treasury yield to end the year between 1.75% and 2.0%. Now, however, there are two key elements suggesting we are unlikely to see significantly higher interest rates by year end: The Delta variant’s impact on economic growth expectations, and the continued demand for U.S. Treasuries by foreign investors. As such, our new year-end target for the 10-year Treasury yield is between 1.50% and 1.75%.

Coming into the year, and into our 2021 mid-year outlook, we expected Treasury yields would move higher than current levels. Higher inflation expectations, less involvement in the bond market by the Federal Reserve (Fed), and a record amount of Treasury issuance this year were all reasons we thought interest rates could end the year between 1.75% and 2.0%. Now, however, there are two key elements suggesting we’re unlikely to see significantly higher interest rates by year-end. The Delta variant’s impact on economic growth expectations and the continued demand for U.S. Treasuries by foreign investors are likely to limit the upside in long-term Treasury yields. As such, we are slightly lowering our year-end forecast for the 10-year Treasury yield. We now believe the 10-year Treasury yield will end the year between 1.50% and 1.75%.

Delta Variant Delying Full Economic Growth Potential

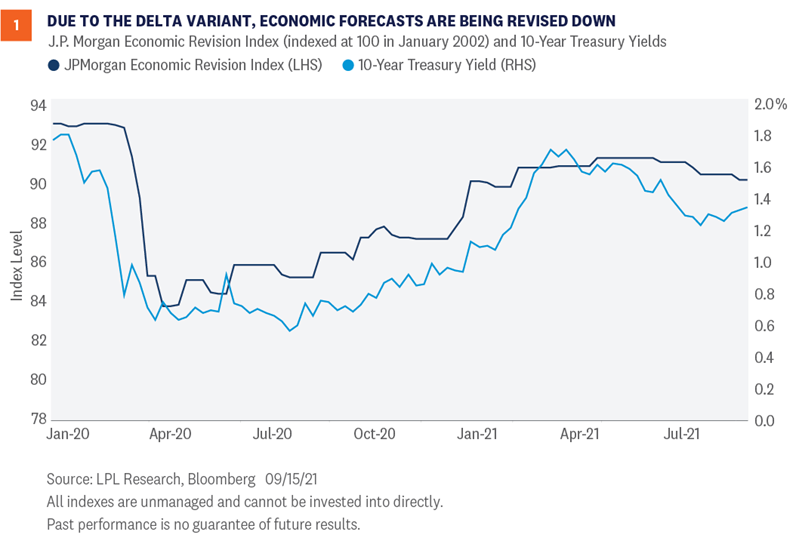

A key variable in determining the direction and level of interest rates is the expected growth rate of the economy. With everything else being equal, if the gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate is expected to increase, long-term Treasury yields tend to increase as well. The reverse is also generally true. Going into the COVID-19 lockdowns, we saw both growth expectations and 10-year Treasury yields fall significantly. However, as seen in Figure 1, after the successful development of the COVID-19 vaccines in early January, GDP growth expectations were generally revised higher (JPMorgan’s Economic Revision Index rises as economists’ expectations for economic growth improve). As such, long-term interest rates generally moved higher as well. However, due to the persistence of the Delta variant, we are starting to see GDP growth forecasts revised lower. That has kept interest rates relatively anchored at current levels. We think any potential slowdown in growth will be temporary, with future growth expectations eventually rising as the impact of the Delta variant wanes and the economy bounces back again, which we think will likely take place over the next six to 12 months. Until then though, long-term interest rates may have difficulty moving significantly higher from current levels.

Foreign Investors Still Incentivized to Invest in U.S. Treasuries

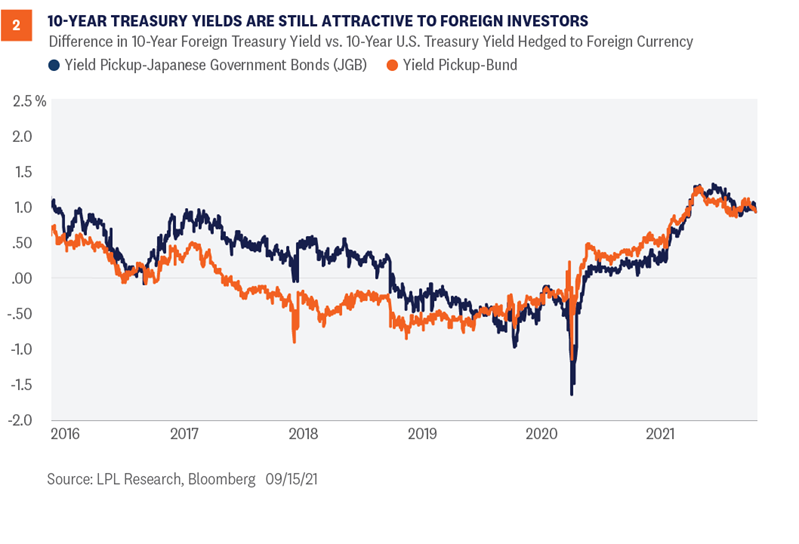

Another key reason we believe interest rates have not moved much higher this year is foreign investors’ interest in the U.S. Treasury markets. Global interest rates remain low by historical standards and compared to U.S. Treasury yields. In fact, a number of countries have 10-year Treasury yields close to 0.0% or even negative in certain countries. Aging demographics and strong social support programs have made many Japanese and European investors look outside of their home countries to help fund underfunded pension schemes. Currently, there remains nearly $15 trillion in negative-yielding debt globally, which makes the 1.33% 10-year Treasury yield (as of September 16) look extremely attractive.

Moreover, when investing in U.S. markets, foreign investors have to be mindful of the currency risk associated with U.S. investments. Because foreign investors’ liabilities are denominated in their home currency, most foreign investors hedge out the dollar risk embedded within U.S. investments. There is a cost to hedging out that risk though, which limits the attractiveness of those cross-border investments. But as shown in Figure 2, even after considering those costs the yield pickup relative to Japanese government bonds (JGB) and/or German bunds can be substantial. Japanese and German/European investors in particular can earn an additional 1% per year by investing in U.S. Treasuries. While that may not sound like much, the alternative for many German/European investors is to pay the government 0.30% per year for 10 years for the right to own that debt. In this low-rate environment, any incremental yield pickup is welcome. As the Fed starts to raise short-term interest rates—likely in 2023—the costs to hedge the currency risk increases. But until then, the incentive for cross-border investment remains, which will likely constrain the amount of upside we will see in long-term U.S. yields through the end of 2021.

All Eyes on the Federal Reserve

The Fed is meeting this week to discuss its ongoing commitment to its asset purchase program. Since March 2020, the Fed has supported the economy and financial markets by purchasing $120 billion in Treasury and mortgage securities, and by keeping short-term interest rates near zero. As the economy continues to recover, however, the need for continued monetary support wanes. Coming into the year, we identified Fed policy as a key risk to higher yields. The last time the Fed was in the position to reduce/taper its bond purchases, then-Chairman Ben Bernanke surprised markets by casually mentioning that the Fed would start to taper its bond-buying programs in the coming months. His comments caught equity and fixed income investors by surprise and both markets reacted negatively—although the equity markets went on to return 30% for the year. While we are in a similar situation today with the Fed likely to formally announce its intentions to taper its bond-buying programs soon, the markets have no reason to be surprised. The Fed has been communicating its intentions to eventually taper bond purchases for several months now. Markets should be well prepared at this point as the Fed learned its lesson from 2013 and has done a much better job communicating its intentions. As such, we do not envision another “taper tantrum” event that causes interest rates to spike higher.

Conclusion

Near-term inflation expectations above historical trends, less involvement in the bond market by the Fed, and improving growth expectations once the Delta variant recedes are all reasons why we believe interest rates will move moderately higher from current levels. We expect the 10-year Treasury yield to end the year between 1.50% and 1.75%. We may see even higher yields next year, but an aging global demographic that needs income, higher global debt levels, and an ongoing bull market in equities (which potentially means more frequent rebalancing into fixed income) may keep interest rates from going substantially higher in 2022 as well.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This material is for general information only and is not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. There is no assurance that the views or strategies discussed are suitable for all investors or will yield positive outcomes. Investing involves risks including possible loss of principal. Any economic forecasts set forth may not develop as predicted and are subject to change.

References to markets, asset classes, and sectors are generally regarding the corresponding market index. Indexes are unmanaged statistical composites and cannot be invested into directly. Index performance is not indicative of the performance of any investment and do not reflect fees, expenses, or sales charges. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results.

Any company names noted herein are for educational purposes only and not an indication of trading intent or a solicitation of their products or services. LPL Financial doesn’t provide research on individual equities.

All information is believed to be from reliable sources; however, LPL Financial makes no representation as to its completeness or accuracy.

US Treasuries may be considered “safe haven” investments but do carry some degree of risk including interest rate, credit, and market risk. Bonds are subject to market and interest rate risk if sold prior to maturity. Bond values will decline as interest rates rise and bonds are subject to availability and change in price.

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (S&P500) is a capitalization-weighted index of 500 stocks designed to measure performance of the broad domestic economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries.

The PE ratio (price-to-earnings ratio) is a measure of the price paid for a share relative to the annual net income or profit earned by the firm per share. It is a financial ratio used for valuation: a higher PE ratio means that investors are paying more for each unit of net income, so the stock is more expensive compared to one with lower PE ratio.

Earnings per share (EPS) is the portion of a company’s profit allocated to each outstanding share of common stock. EPS serves as an indicator of a company’s profitability. Earnings per share is generally considered to be the single most important variable in determining a share’s price. It is also a major component used to calculate the price-to-earnings valuation ratio.

All index data from FactSet.

Please read the full Midyear Outlook 2021: Picking Up Speed publication for additional description and disclosure.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial LLC.

Securities and advisory services offered through LPL Financial (LPL), a registered investment advisor and broker-dealer (member FINRA/SIPC). Insurance products are offered through LPL or its licensed affiliates. To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor that is not an LPL affiliate, please note LPL makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not Insured by FDIC/NCUA or Any Other Government Agency | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | Not Bank/Credit Union Deposits or Obligations | May Lose Value

RES-894867-0921 | For Public Use | Tracking # 1-05191527 (Exp. 09/22)